…

…

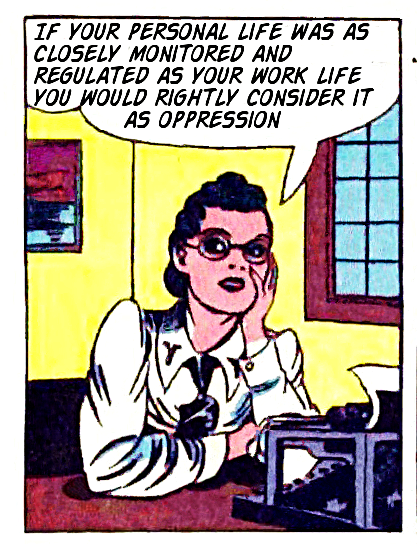

work is a source of freedom-undermining domination in our lives. Freedom is a central good in liberal societies. If a government fails to protect our freedom, we often deem it unjust or illegitimate. Of course, it is impossible to completely eliminate unfreedom – so many things threaten and impinge upon it – but a better or worse job can be done. A government that arbitrarily takes away our rights and privileges, that subjects us to random searches and seizures, and is run by unelected and unaccountable officials would be much worse than a democratically elected government that abided by the rule of law. It’s ironic then that we tolerate governments of the former type it in one environment that we spend most of our (non-sleeping) adult lives: work.

As Elizabeth Anderson points out in her 2017 book Private Government, employment contracts frequently grant employers the power to significantly undermine their workers freedom. Many low paid workers are subject to random bag searches and drug-testing; their work schedules are managed in arbitrary and often debilitating ways through a combination split shifts and “just in time” scheduling; they are also subjected to more and more totalising forms of surveillance and monitoring. Not only are they frequently asked to use tracking devices during the working day; they also now rewarded – through so-called “corporate wellness” programs – for using them outside of working hours too. One of my favourite examples is the sleep monitoring program introduced by the insurance company Aetna that paid workers a bonus if they could prove they slept at least eight hours a night. Employers use their powers to discipline and control workers, ultimately by stripping them of their livelihoods.

the “colonising” power of work, occupies our mental space. We spend a significant amount of time working, of course, but we also spend a significant amount of time thinking about, preparing for and recovering from work. For knowledge workers like myself, the problem is particularly acute. Our productivity is not obviously linked to the number of hours we “clock in” on a given day. Indeed, the very notion of “clocking in” is alien. There is no meaningful upper limit on the number of hours I can spend reading the latest research and writing my own papers. The latest, career-changing insight could be right around the corner. This realisation results in a significant amount of guilt when I am away from my desk. When I’m not working, my mind is still troubled by work. This is despite the fact that my contract stipulates that I am only being paid for a 37.5 hour working week.

The colonising powers of work express themselves most keenly in the “employability” agenda. We are now disciplined from an early age to learn the language of employability, to constantly build and manage our CVs so that we are attractive prospects for employers. The intrinsic merits of activities are commonly overlooked or ignored in favour of their instrumental benefits for employability. People run marathons and raise money for charity not simply because they enjoy doing those things, but also because it provides evidence of their seriousness and diligence to potential employers. Anyone who works in education will know how common and soul-destroying this logic is. Students are trained to organise their extra-curricular activities into “employability portfolios” and resist learning anything that does not contribute to their employability.

https://www.philosophersmag.com/essays/184-the-case-against-work